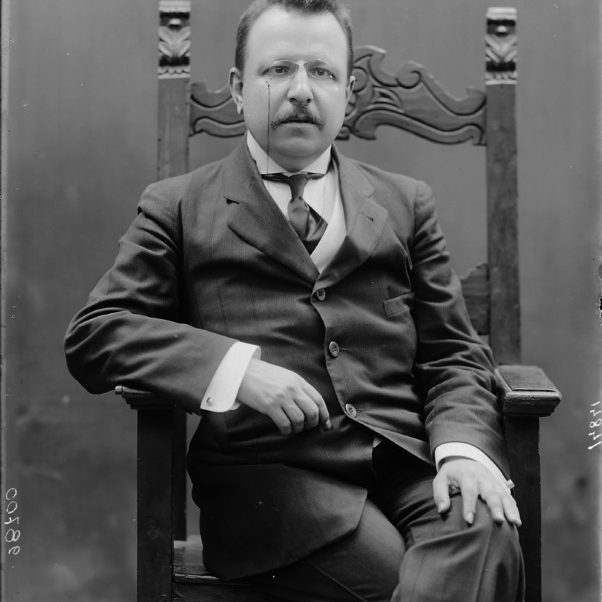

Italian political philosopher Benedetto Croce is one of the most referenced figures in The Prison Notebooks, albeit one whom Gramsci viewed as being too removed from Italian political life.

The Prison Notebooks and Intellectuals

By Dillon Causby

The Prison Notebooks and Intellectuals

On March 19, 1927, Antonio Gramsci, while awaiting trial, wrote a letter to his sister-in-law, Tatiana Schucht. In this letter, Gramsci described his desire to embark on an ambitious intellectual project that would “...absorb and provide a center to [his] inner life.” He listed four subjects that he would systematically study over the span of his potential prison sentence. Of the subjects listed, the first was “…a study of Italian intellectuals, their origins, their groupings in accordance with cultural currents, and their various ways of thinking…” (Gramsci 1927, 79). The ambitious project Gramsci described became the basis for The Prison Notebooks. However, of the four subjects he originally listed, only the first, a study of Italian intellectuals, would be prominent.

At first glance, a study of Italian intellectual development appears to be an unusual subject for a Marxist theorist to be studying. Other prominent Marxists of his day, such as Bhukarin, Luxemburg, or Trotsky, did not view this subject as important. However, the development and practice of intellectuals is crucial in Gramsci’s understanding of historical development. Of all of Gramsci’s theories, perhaps his most famous is the theory of hegemony, the idea that the ruling class does not exercise its rule by force, but by shaping the predominant culture and beliefs of a society. In Gramsci’s view, intellectuals played a critical role in creating and proliferating a hegemony of ideas, and would be crucial in the establishment of a socialist society

Defining Intellectuals

Like many other terms used by Gramsci, the term ‘intellectual’ takes on a somewhat different meaning in The Prison Notebooks. While the title of intellectual is usually given to the great thinkers of a society who have had a defining influence on how we view the world, Gramsci describes everyone as an intellectual because, in his view, every human must exercise critical thought. However, while everyone in society is an intellectual, not everyone in society exercises the “function” of an intellectual, which according to Gramsci, is to provide legitimacy to the existing order (Schwarzmantel 2015, 73). If the hegemony of a dominant group is secured primarily by consent, then intellectuals play a crucial role in justifying their rule and framing it as natural.

Gramsci distinguishes between “organic” and “traditional” intellectuals. According to Gramsci, every social class naturally creates its own collection of intellectuals. These are described by Gramsci as organic intellectuals, who give to their social class a sense of consciousness and meaning. Traditional intellectuals, on the other hand, are a group of intellectuals who are somewhat removed from the rest of society. While these intellectuals view themselves as independent from the dominant class, Gramsci believes that in order to truly reshape a society, the dominant class must "absorb" these traditional intellectuals (Schwarzmantel 2015, 77).

The Working Class and Organic Intellectuals

As a socialist, Gramsci was concerned with how the working class, or proletariat, could achieve hegemony over the ruling class, or bourgeoisie. In Gramsci’s view, the working class must have its own set of organic intellectuals to educate the proletariat and instill in its class consciousness. The main engine of this working class education would be the political party. Rather than operating as a mere parliamentary grouping, the party would be a center of political education that would allow the working class to move beyond what Gramsci called the “economic-corporate level,” or motivation by purely economic interests, into the realm of political emancipation (Schwarzmantel 2015, 83). This idea is somewhat reminiscent of Lenin’s idea of the vanguard party in his seminal pamphlet What is to be Done?. However, while Lenin believes that these intellectuals must come from elite circles outside the working class, Gramsci believes that these intellectuals must be developed from inside the working class itself.

Citations

Gramsci, Antonio. 1975. Letters from Prison. Translated by Lynne Lawner. London, England: Jonathan Cape.

Schwarzmantel, John. 2015. The Routledge Guidebook to Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. London, England: Routledge.

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.