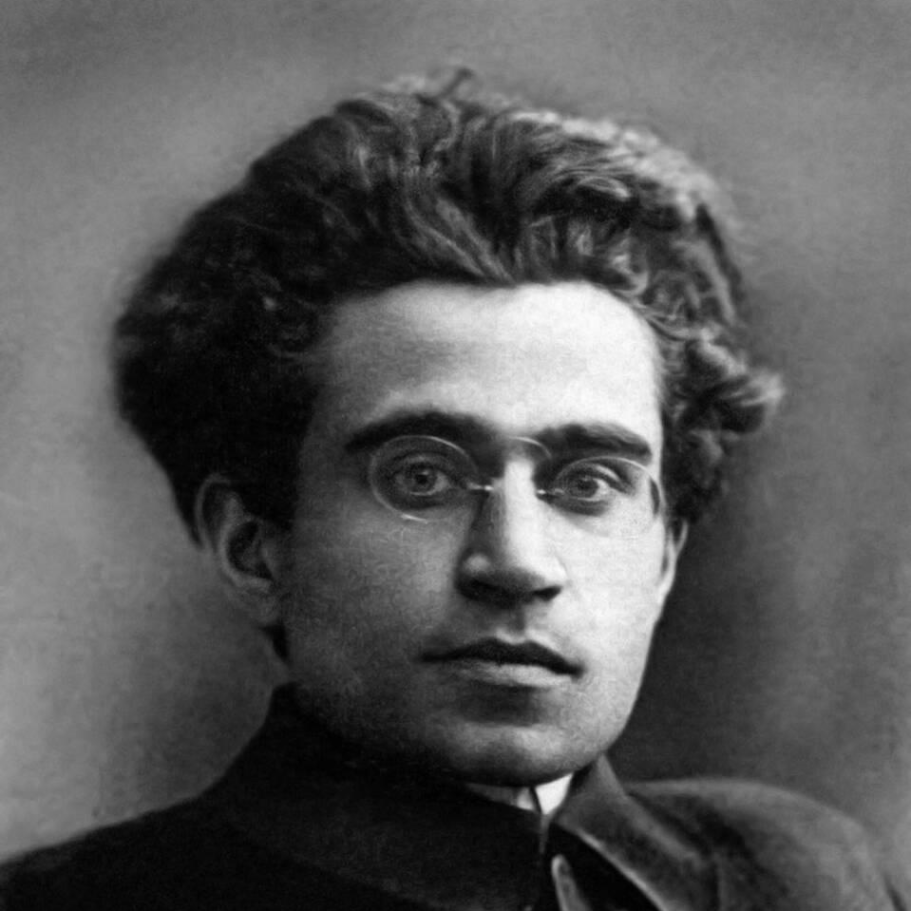

Who Was Antonio Gramsci?

By Dillon Causby

Antonio Gramsci was one of the most prolific and creative political thinkers of the twentieth century. Although his ideas did not receive considerable attention during his lifetime, the concepts contained in his magnum opus, The Prison Notebooks, provided inspiration for a generation of political scientists, theorists, and politicians on both the left and right. From the oppressive conditions of an Italian fascist prison, Gramsci developed an analysis of history, politics, and Marxism that was wholly original. The brilliance of his work lies in the fact that The Prison Notebooks not only serve as a guide to understanding the history and politics of the early twentieth century, but also as a guide to understanding contemporary society.

However, in order to understand The Prison Notebooks, a context of Gramsci’s life and intellectual trajectory is needed. As noted by John Schwarzmantel in his book, The Routledge Guidebook to Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, Gramsci found himself in two prisons while writing his seminal work: The literal fascist prison he lived in, and the ideological prison of his party, the Communist Party of Italy (PCd’I) later known as the Italian Communist Party (PCI) (Schwarzmantel 2015, 45). This is because throughout his political career, Gramsci often found himself at odds with the orthodoxies of the socialist movement he was passionately committed to. During his time in the Italian Socialist Party (PSI), Gramsci’s opposition to Orthodox Marxism made him a brief ally of the very man who would come to imprison him, Benito Mussolini (Berman 2006, 76). While writing from prison, his diversion from the political line of the PCd’I and USSR forced him to use coded and cryptic language, making the Notebooks a text that is at times, difficult to understand. In order to understand and appreciate the content of his Notebooks, a brief overview of his life and development is required.

Antonio Gramsci was born in 1891 on the Island of Sardinia. A committed academic all his life, Gramsci studied linguistics and philology at the University of Turin. It is here that he became involved with the Italian labour movement and joined what was at that time the main socialist force in Italy: The PSI. He became a writer for the socialist paper Avanti!, meaning “Forward!”. Previously, the editor for Avanti! had been a little known Italian socialist known as Benito Mussolini (Schwarzmantel 2015, 5). It is in this paper that Gramsci began articulating a version of Marxism that was different from the dominant Orthodox interpretation. Rather than seeing economic forces as the sole driver of history, Gramsci saw Marxism as a “...expression of human will and creative action” (Schwarzmantel 2015, 6) It was Mussolini and Gramsci’s shared disdain for Orthodox Marxism that for a time made them brief allies. However, they would go down very different ideological paths.

T he years following the First World War were crucial to Gramsci’s ideological development. The Russian Revolution of 1917 and the establishment of the Soviet Union led Gramsci to become less favorable to liberalism, and more open to a new kind of socialist state created in the mold of the Bolsheviks. Furthermore, Gramsci viewed the factory council movement that emerged in Italy during The Biennio Rosso (1919-1920) as the beginning of a new democracy, different from the parliamentary democracies of the pre-war years (Schwarzmantel 2015, 11). Gramsci saw the political party as instrumental in establishing a new socialist state. However, many others within the PSI disagreed with Gramsci’s activist stance. Following the split in the PSI over whether or not the party should join the newly formed Communist International, Gramsci, along with others, left the party to form the PCd’I.

The factory council movement became a major inspiration for Gramsci, who viewed the factory council as the principal unit in a new kind of socialist state. However, the socialist revolution that Gramsci believed to be imminent never came to pass, and in October 1922, Mussolini had taken power in Italy. The question of why the factory council movement failed, and why a fascist state emerged, became a central point of analysis in The Prison Notebooks.

From 1922 to Gramsci’s arrest in 1926, the PCd’I was rife with infighting and factionalism. There was disagreement over whether the PCd’I should stand alone against fascism, or form a “united front” with other anti-fascist parties. Gramsci led the force within the party to accept the united front policy, and won (Schwarzmantel 2015, 19). However, Gramsci and the PCd’I were often forced to pick sides in conflicts within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which had a predominant influence in the Communist International. In 1924, Gramsci was elected as a parliamentary deputy, and thus protected by parliamentary immunity. However, Gramsci was nonetheless arrested by the fascist police on November 8, 1926. In what amounted to a show trial, the prosecutor said “we have to stop this brain working for twenty years.” On June 8, 1928, Gramsci was sentenced to prison for twenty years, four months, and five days (Schwarzmantel 2015, 39).

It was during this time in prison that Gramsci wrote The Prison Notebooks, a collection of notes, jottings, and essays which in total, cover over 2,300 pages. These notebooks were never meant to be published. Ideas explored in one notebook are later mentioned in another. Furthermore, Gramsci borrows terms that previously existed in political theory, but redevelops them in a wholly original way. This lack of structure makes The Notebooks somewhat difficult to understand. However, the overarching purpose of these notebooks is to understand how the workers movement of The Biennio Rosso failed, how Mussolini came to power, and what socialists can do to create a new society.

Works Cited

Berman, Sheri. 2006. The Primacy of Politics: Social Democracy and the Making of Europe’s Twentieth Century. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Schwarzmantel, John. 2015. The Routledge Guidebook to Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks. London, England: Routledge.

©Copyright. All rights reserved.

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.